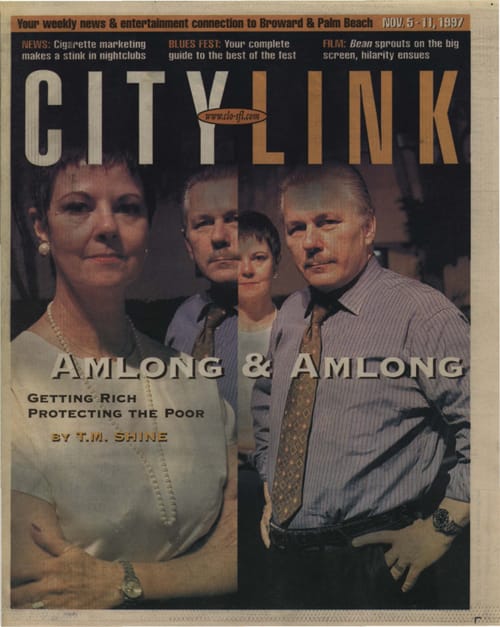

AMLONG & AMLONG

AMLONG & AMLONG

Getting Rich Protecting the Poor

by T.M. Shine

Cover Story

Underdog vs. Wolves

From Abused Prison Inmates to Foul-Mouthed Teens,

the Amlongs Are on the Side of the Angels

Opening Argument:

"Here's the short version," says attorney William Amlong to the jury:

The appliance store had a show biz theme. The client , the plaintiff , was a "show stopper", meaning she always got two thumbs up for her job performance. Then something happened. He hesitates, only slightly, to let the jury know the words that are about to come out of his mouth are not his. When Amlong utters the word "pussy" it belongs to the man who supervised his client. It belongs to the company that hired that man and allowed him to repeatedly sexually harass his client until she became suicidal. It belongs to an endless trend that has overcome the workplace. But it does not belong to him. Amlong paces before the jury, one hand clenched behind his back, a microphone in the other. He's got a boxers build that's neatly packed into an expensive suit.

For a moment, it appears as if he's going to try the whole case in the opening argument but he quickly moves to sum things up with a series of barn-size blowups of interoffice complaints ignored by management while his client suffered.

At his side, gracefully lifting the bulky memos like a game show assistant, is his law partner and wife, Karen Coolman Amlong. Cat-eyed and sleek, she looks at William admiringly as he addresses the jury. Her gaze is comparable to that of a mesmerized Deepak Chopra disciple. It's a look the jury soon mirrors.

For the moment, this is her role. William is the grand storyteller so he always does the opening. She is the artist who takes all the frayed ends and ties everything together in the closing arguments.

In between, they will crisscross, she taking on the technical aspects of the case, both of them grilling the defendants on the witness stand. "Some people are easily intimidated by an attractive woman in a red power dress and stiletto heels", William says. "In one case she had the president of a subsidiary of Westinghouse stuttering up there in the box."

Glenn Caddy, a Fort Lauderdale psychologist who has seen the Amlongs in action many times, says there is something entertaining, powerful and persuasive about their presence in a courtroom.

"Their cross-examinations are done with such intellectual precision, it's more like an opera than a courtroom battle," Caddy says.

As the Amlongs confer at the conference table, the jury is attentive to their demeanor. They watch as the couple leans in for tight whispers, but despite their 15 year marriage, the scene comes across as more professional than cozy.

"They see us as more than lawyers," Karen says. "They see us as a team, a family fighting together."

The Fort Lauderdale couples solid relationship bathes them in intrigue, takes them above the pettiness of the law.

"Being a husband and wife team adds a little theater, people are more curious, like we are TV characters," William explains.

Amlong & Amlong, the Hart to Hart of civil trial lawyers.

Made for TV

They are fighting for the little guy and making lots of money doing it. Enough for the Porsche Carrera, the house in Rio Vista, late dinners at San Angel and summer skiing in Chile. They have got the kind of personalities that could easily be inflated to fit the small screen. It is not beneath her to step up at a deposition and blast another attorney for being a short guy with a small dick. It is not above him to drive through a garage door to release a little tension during a big case, or perhaps an argument with his lovely wife.

To play off the hard edges, they have got their soft sides covered with four dogs and three cats waiting for them at home, if and when they ever get there. And there are those cool nuances just below the surface, like their phone number "462-1983" which is in honor of the U.S. Civil Rights Act (482 USC Sect. 1983).

Since the mid-80s, the Amlongs have been at the forefront of high-profile civil rights cases, both together and individually. Many of them you will recall: suing prison officials for allowing the rapes and beatings of inmates by other inmates at Glades Correctional Institution, police violating citizens civil rights in Davie, racial bias within Broward County's Office of Environmental Services and, most recently, June Amers fight against the state law banning homosexuals from adopting children.

But the backbone of their practice are horribly routine employee issues that rarely make the headlines: age and race discrimination, sexual harassment, pension discrepancy battles, wage rip-offs.

Cases like the one starring the "show stopper" saleswoman, who suddenly found herself the victim of debilitating harassment. A case where they can go before the jury and sum it up by saying: A Bottom line: He still works there, she has not been back since.

"And pick up 144 and change," William grins. Yes, he means $144,000, for the client and for the firm.

Perhaps their Yellow Page Ad says it best: "REPRESENTING WORKING MEN AND WOMEN AGAINST MANAGEMENT."

"Corporations see employees as germs," William says matter-of-factly, "and it's hard to argue with a gentleman who holds such beliefs."

The Amlongs ---she's 50, he's 52 --- love to get up in the morning and this is why. "We're leftover 60s kids who get to screw with authority and make money doing it."

It's a love story

It's after 7 P.M., but it looks like the day is beginning at Amlong & Amlong. The lobby of their second floor offices on Northeast Fourth Street is dark (no more appointments) but the work area is lit up like a Kmart. Clerks are shuffling about, phone calls are still being made.

"If a legal question comes up during a trial, we're big on midnight memos," Karen says. "It's not all that uncommon to work through the night and then just change clothes and go to the courthouse."

Piles of paperwork, each representing an individual case, wrap around the curve on Karen's desk like a small chain of mountains.

It's late in the day, but they don't mind talking about themselves into the night because there is no place to get to, no aerobics at the gym, no movie to catch. The only place to go is back to work.

"This is how we do it," Karen says. "When we're in town, we work seven days a week, night and day. When we're not here, we ski."

Not a bad system. But one only two soulmates could probably survive.

How did these two find each other?

Here's the short version: They didn't.

At least not in their first lives. Both grew up in South Miami, but never crossed paths in their early years. "Even if we had, Bill wouldn't have been the type of boy my mother would have let me associate with," Karen says.

She has been married twice previously and has two grown sons. One of whom she breast-fed in the halls of the state House, when at age 27, she was elected Browards first woman legislator in 1974.

William was an investigative reporter for The Miami Herald when he first laid eyes on her. "I was in Tallahassee working on a banking story in 1975 when I spotted all the other reporters sniffing around this freshman legislator," he says.

He waited patiently for them to clear out and then introduced himself. "We clicked right away, Karen says."

Clicked in the way that you were two smart and sophisticated professionals who could relate well to each other?

"No, we really clicked," William says.

But they were both married to other people at the time and just slipped back into the '70s, which wasn't easy for either of them.

Both went through divorces and other serious relationships. William continued to report on high-profile stories all over the world, a passport always tucked in his back pocket. Karen left the Legislature after one term, retired to law school and eventually, a struggling practice.

Then, one afternoon, seven years after their initial meeting, Karen was walking down the boulevard in Coral Gables... "And here come Amlong," she says.

Big click. A worlds-colliding click.

The big bang, but they were still a long way from becoming the two-headed, four-legged, discrimination-fighting skiing juggernauts they are today.

The practice

By the time they met the second time, William was contemplating law school. "It was self-defense. You have to be an attorney to live with one," Karen laughs.

Actually, William had already been accepted and saved enough money for his first year at Novas law school. After they married, they decided he could work in her office until he finished school. They had a plan.

For the first year, that is.

"But business wasn't that great. I was just an itty-bitty baby attorney myself," Karen says.

By the time William's second year of tuition was due, it was no can do.

"But things have had a way of falling in place for us," William says.

In the case of his tuition, it was a horse that fell into place. They were at Hialeah racetrack, meeting with a client who had been banned from another track, when William took a liking to an Irish horse from Argentina in the ninth. "I put $300 across the board, he says. The horse moved like he had jet engines attached to him and we won $3,000 to pay my tuition."

Karen had started in marital law, but the practice was gradually moving toward civil rights issues. After the two of them teamed up, it was a natural progression. Karen had been a member of NOW for more than 20 years and had previously helped operate a crisis center for rape victims in an old house on Sistrunk Boulevard.

"And as a reporter, I was always covering civil rights and union stuff," William says.

At first they didn't think they could make a living fighting for the little guy because the awards generally weren't huge, but, as usual, that also fell into place.

In 1992, Karen won a landmark sexual harassment case representing a Miami woman against a movie company executive. The award was a whopping $1.3 million, which included punitive damages.

"Then, referrals really starting coming in," William says.

Roberta Covey, a Fort Lauderdale attorney who also handles employee issues, remembers it as a monumental case. "It really opened up our area of law," she says. "The Amlongs have become the authorities in the field."

With four associates, they now get about 30 calls a day which are screened by a paralegal. Of those, they take about one out of 100.

They can afford to be choosy.

"Im not sure we could make more money in another type of law," William says. "But we could certainly make easier money."

The bad guy and the femi-Nazi

"Our strong reputation isn't based so much on winning ,we lose a lot of cases as it is on the fact that were always ready to go to trial," William says. "The defense bar knows full well were not afraid to go pick a jury tomorrow morning.

Local defense attorney Mike Burke, who has had a sort of win, lose and draw relationship with the Amlongs, says, "In my experience with them, they are always prepared to go to trial and when they get there... well, let me just say this, they are very worthy adversaries."

Covey says, "In a time when lawyers have a reputation for settling for being money grubbers the Amlongs are a relief."

The Amlongs see corporate defense attorneys as emperors of the dark side. They respect very few.

"Defense attorneys are like an evil priesthood," William says. "Firing old people is a celebration. Harassment is sacred."

William has a reputation for getting in pissing matches in the legal trenches. "He's gotten into physical altercations," Karen says. "I often look like the good guy to his bad guy."

"That's when she's not being seen as some sort of femi-Nazi," William points out.

But their reps are worn with honor. Especially since we're dealing with scum, William says of the corporations that continue to devalue the American worker.

They argue that companies have put safeguards, policies and training in place to combat discrimination and harassment, while at the same time, flagrantly continuing to ignore the seriousness of the issue.

"These things don't happen in companies where there is a culture of respect," William says.

But sexual harassment cases just keep coming and coming and coming across their desks.

"It's absolutely mind-boggling," William says. "And we've had a string of cases where it seems like all the guys are going to the same Hustler school of behavior."

Addys Gonzalez, a Miami saleswoman who was the victim of sexual harassment, says before she contacted the Amlongs she was made to feel guilty herself, like a rape victim.

"Because everybody's afraid of telling the truth. They think they might lose their jobs if they get one of the bosses in trouble," she says. "Even my own brother said, Leave it alone, it happens all the time, there is nothing you can do about it."

She ended up doing plenty about it when the company she worked for wouldn't come up with a fair settlement. They went to trial where she got to see the human resources manager who had ignored her complaints, squirm around in the hot box. Revenge was sweet.

"It's about fighting back. Being vindicated," Karen says.

Age discrimination also has become predominant in their practice. It looks good on the surface ,out with the old in with the new. "But it's cruel and I love those cases because everybody gets old," William says. "Lots of jury sympathy."

Leonard Lowinger, who's now 65, went to the Amlongs when the optical company he worked for decided to "throw him away," as he puts it.

"But they didn't just accept my case," he says. "I had to take a lie detector test and see a psychologist first. They were very compassionate, but very careful."

In a time where lawsuits have become overly frivolous, the Amlongs want to be positive they're taking on legitimate cases before they put their reputations on the line.

"You not only want to weed out the frivolous, but when you're going to make severely damaging accusations and people's reputations are on the line, you want to be as diligent as possible," Karen says.

Not that they haven't had their share of cases that make one go, "Oh, come on," like "Woman Sues NBC, Says Bosses Were Too Lenient."

"We lost that one," William sighs. "But it was interesting."

Aside from the occasional bizarre case, they say there are no new trends in their line of law, only more of the same.

"If anything, we've learned how the abuse spreads," William says. "Early on, I tried a lot of police brutality cases against street cops and now these monsters have moved up the chain of command and are bullying their employees the same way they bullied the citizens on the street."

In the simplest of terms, the Amlongs say they are "anti-bully," that's what they are.

They sue bad behavior.

Work amounts to a hill of gourmet beans.

A homeless person has taken up residence in an alcove outside the Amlongs office and the situation offers up the perfect example of their attitude. They have no problem with a fellow human being taking shelter from the storm, even if its at their inconvenience, but they also have no problem stepping past him into the luxury cars parked in their personalized spots.

The Amlongs will stand on the sunny side of the high road and say it is all about seeing that people are not judged by race, sex, creed or color and that the judicial process can make a difference.

But at the same time they are not ashamed that the process is allowing them to lead the high life.

"We're amazed by the number of sexual harassment cases that keep coming, but we're glad," Karen smiles. It's their business.

They like the game and they play it well. "It's fun," Karen says.

So, they make their money, go to fancy dinners, donate to charity and ski around the world. Canada is the next stop.

"But most of the work you do you can feel good about. You're fighting to get somebody's job back or get them fair compensation. You're helping them make a change in their life," William says. "Even when you lose, you can feel good about yourself."

He recalls a harassment case in which he represented a gay woman who worked on the presses at the Sun-Sentinel. "We lost, but fighting back made her feel better, it empowered her," William says.

To them, the little people are big people, too. "No one is untouchable in corporate America. We still represent our share of waitresses and office workers, but we also have plenty of surgeons, VPs and other lawyers," William says. "With the new medical system, Dr. Welby is now being discriminated against."

These days, 75 percent of the Amlongs caseload is employee related. It's enough to keep them going 27 days straight, starting cases together with one of them dropping out in the middle to start another and then coming back to close.

"We're adrenaline junkies and then we crash," Karen says.

In a profession that even the Amlongs say is full of snakes, they're just happy that they haven't become jerks, or lawyers who walk around thinking they're God almighty.

"I don't know where some attorneys get the attitude that they're above other people," William says. "It's the only profession with a postgraduate program that tolerates. They have standardized dumbed-down testing. To me, a 66 does not equate to canonization."

Its about 8:30 P.M., when Karen's son, Clay Coolman, who is their office manager, pops into her office to say he's going to call it a night. "I can't keep up with them," he says. He's 27.

Tonight, the Amlongs will climb a few of the mountains on their desks and then cruise out in the Porsche and catch a late dinner of expensive gourmet Mexican. Treating themselves for being good employees.

Do they deserve it?

Do they deserve it? Do all corporations see employees as germs?

Reprinted with permission from City Link Magazine, in which this article appeared in the November 5-11, 1997 issue.

Just a Handful of Memorable Cases the Amlongs Have Either Together or Individually Participated In:

1985 - Class action suit on behalf of 10 inmates is filed against officials at Glades Correctional Institution claiming they were negligent in protecting the 10 from inmates known as wolves who raped and beat other prisoners with impunity. What they really need to do with GCI is just bulldoze it, William Amlong says.

1989 - Class action suit filed against Pratt & Whitney for laying off employees who refused to accept early retirement packages, and then hiring younger less costly employees. That's a sure way of cutting down overhead. Fire all its older employees, William says.

1990 - Class action suit filed against Gov. Bob Martinez for violating the constitutional rights of work-release prisoners. The governor has turned the management of Florida's prison system over to his re-election campaign, William says.

1992 - Miami woman is awarded $1.3 million in sexual harassment case against a movie company executive. It was a high-profile case and I think it raised a lot of women's consciousness about this, Karen Coolman Amlong says:

1992 - Woman who worked for NBC's Miami Bureau sues employer for being too lenient. The argument is that had she been disciplined or fired by NBC, she could have improved her performance. The law doesn't say that a woman should be treated better. It says that a woman should not be treated differently. If you put women on a pedestal, you're not doing them any favors, William says.

1992 - Workers for Broward County Office of Environment Services file complaints charging racial discrimination, claiming minorities are being passed up for promotions. It's real white at the top. [At the bottom], it's real black. You don't have a learning curve over there. You have a brick wall, William says.

1992 - Jury finds that Davie police officer violated the civil rights of a 16 year old girl while arresting her for cursing, but declines to order him to pay damages. But the suit wasn't about money, and civil rights don't have to be about money, William says.

1994 - Two former lifeguards are awarded $47,500 in a sexual harassment lawsuit against the city of Boca Raton and two male supervisors. I consider it to be the vindication of the rights of women who work for the city of Boca Raton not to have to put up with guys who think of them as sex objects instead of co-workers, William says.

1997 - Broward County Circuit judge denies a request from a lesbian mother in Weston to declare unconstitutional a state law banning homosexuals from adopting children. The children of the State of Florida are the losers with this decision, Karen says.

1997 - Fort Lauderdale woman goes to trial after filing a lawsuit against the Florida Board of Regents, accusing them of punishing her for complaining about a supervisor's advances. She just wanted him to behave himself, Karen says.

1997 - Female police officer with Hollywood Police Department is awarded $100,000 after filing a lawsuit claiming that she was subjected to sexual harassment on the job and that her co-workers took steps against her when she testified in the harassment trial of a fellow officer in 1994. These were cowardly, anonymous things, Karen says. None of these guys had the guts to go up to this 100 pound woman and say, you're a real SOB for ratting me out.